By Tony Okpala

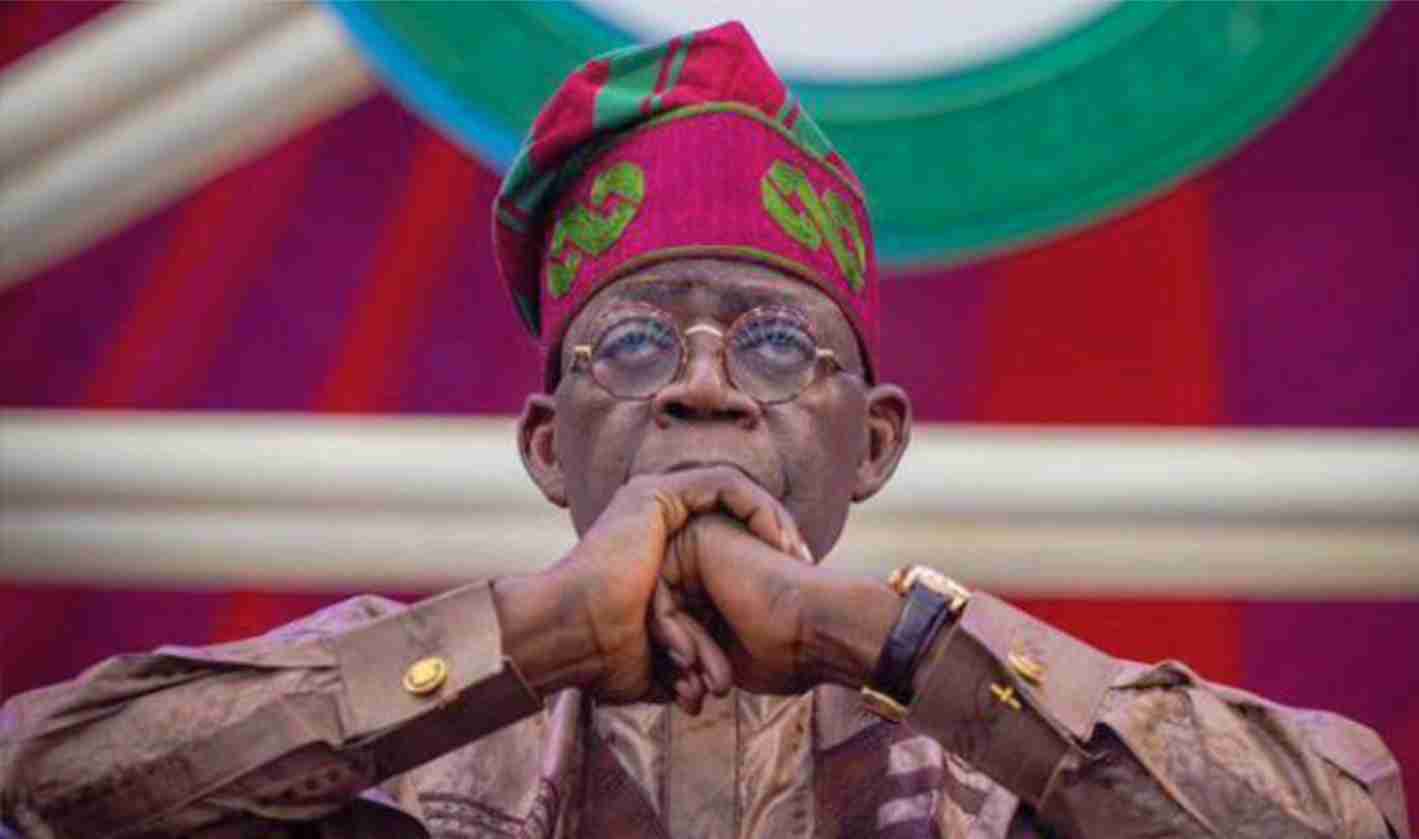

At a recent forum hosted by the Lagos Business School, a critical remark by Catherine Pattillo, Deputy Director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), sent ripples across Nigeria’s economic and political landscape. Pattillo claimed that the economic reforms implemented over the past 18 months under President Bola Tinubu’s administration have not yielded desired results. This statement, stark in its delivery, underscored both the challenges facing Nigeria’s economy and the complexities of IMF-Nigeria relations.

The reforms in question—subsidy removal, currency harmonization, and increases in utility tariffs—have undeniably imposed severe hardships on Nigerians. Yet, these measures are far from arbitrary; they align closely with long-standing prescriptions championed by the IMF. The irony of Pattillo’s critique lies in the apparent dissonance between the IMF’s advocacy for such policies and its willingness to distance itself when these reforms falter.

The gathering at Lagos Business School, attended by stakeholders from various sectors, quickly transformed into a forum for collective discontent. Criticism of the government’s reform strategies flowed freely, painting a bleak picture of the nation’s economic trajectory. However, this setting was emblematic of a deeper paradox: many of the critics, including prominent economists aligned with the Lagos Business School, have historically supported the free-market policies now under scrutiny.

The event was ostensibly organized to unveil the IMF’s economic outlook for sub-Saharan Africa. Yet, it also became a platform for reflecting on the efficacy—or lack thereof—of the liberal economic strategies Nigeria has adopted. Despite the harsh realities facing Nigerians, the IMF’s recommendation remains consistent: deeper, more extensive reforms. This begs the question of how much more hardship can be asked of a population already stretched thin.

The IMF’s history in the global South is marked by controversial policies that often prioritize fiscal discipline over social welfare. In Nigeria, its influence dates back to the Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) of the mid-1980s, a period many associate with economic decline. Critics argue that the IMF’s neoliberal approach—characterized by subsidy cuts, deregulation, and privatization—frequently exacerbates inequality and poverty.

Recent developments highlight the IMF’s tendency to oscillate between praise and criticism. In October, Indermit Gill, the IMF’s Chief Economist, commended President Tinubu and Central Bank Governor Yemi Cardoso for implementing bold reforms. He urged Nigerians to exercise patience, suggesting that tangible benefits might take as long as 15 years to materialize. Weeks later, however, another IMF official, Abebe Selassie, distanced the institution from these very reforms, describing them as the government’s domestic decisions.

This mixed messaging raises fundamental questions about the IMF’s role in shaping Nigeria’s economic policies. Are its prescriptions tailored to Nigeria’s unique socio-economic context, or are they part of a broader template that overlooks local realities? Furthermore, how should Nigeria balance the need for fiscal sustainability with the imperative to protect its citizens from undue hardship?

President Tinubu’s administration finds itself at a crossroads. While the government has shown a willingness to embrace difficult reforms, it must also contend with growing public dissatisfaction and skepticism about the IMF’s motives. Nigerians deserve policies that prioritize long-term development without compromising immediate welfare.

As the debate continues, it is crucial to reassess not just the reforms themselves, but also the external influences that shape them. The IMF’s input can serve as a guide, but Nigeria’s path forward must ultimately reflect the aspirations and resilience of its people. After all, no reform can succeed without public trust and inclusive economic growth as its foundation.